The Rise of Sustainable Building Ordinances: Benchmarking, Audits and Retro-Commissioning, and Building Performance Standards

Authors: Carli Schoenleber, Dana Weiss, Kelsey Ceccarelli, Sydney Armitage, and Rimzhim Mazumdar

September 5, 2024

This article was featured in GRESB Insights — see publication here.

Highlights

In the past two decades, cities and states in the U.S. have significantly expanded sustainable building ordinances that focus on benchmarking, audits and retro-commissioning, and building performance standards (BPS).

BPS are a more recent development, requiring building owners to meet strict greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or energy intensity targets, or else pay significant penalties. New York City, Boston, and Denver have standards with interim target deadlines for owners between 2024 and 2025.

By establishing a carbon price via penalties for non-compliance, BPS present climate transition risk for building owners. Mitigating transition risk from BPS is complex because buildings vary significantly in their costs for compliance.

Each jurisdiction offers a variety of resources to aid owners in complying with BPS, including technical guidance, trainings, flexibility measures, and options to adjust emissions or energy intensity limits.

Introduction

In response to the growing imperative to address climate change, the U.S. has witnessed a significant rise in sustainable building ordinances over the past two decades, focusing on energy and GHG emissions benchmarking, energy audits and retro-commissioning, and energy and GHG emissions BPS.

This transformation began voluntarily within the commercial real estate sector in the early 2000s, driven by initiatives such as the EPA’s ENERGY STAR® Certification, which initially helped property managers enhance building energy performance. These practices gradually evolved into mandated regulations at municipal, county, and state levels to help jurisdictions monitor building-related emissions and achieve their own climate goals. Since 2008, when Washington, D.C., and Austin, Texas, became the first U.S. cities to mandate energy benchmarking, at least 43 other cities and states have adopted similar ordinances. [1]

Benchmarking laws require commercial, multifamily, and industrial building owners to track and report on energy and, in some jurisdictions, water consumption. Although benchmarking laws make up most of these ordinances, there is also increasing emphasis on building audits and retro-commissioning, along with BPS. Building audits entail formal evaluations of a building's energy usage, while BPS mandate that buildings meet energy or GHG emissions targets aligned with their jurisdiction’s climate objectives.

BPS are profoundly transforming the real estate industry by demanding more than just transparency in building operations. Functioning like an energy code for existing buildings, BPS require property owners to meet strict emissions or energy efficiency targets, often necessitating significant facility updates, such as retrofitting HVAC systems or adding insulation. By implementing both energy codes for new buildings and BPS for existing ones, jurisdictions can ensure that all buildings contribute to environmental goals.

Learn more about the National BPS Coalition

With approaching deadlines and the potential of substantial penalties for non-compliance, these standards are creating a heightened sense of urgency among real estate owners. Many are now keenly focused on determining which of their assets may be subject to these laws, understanding how compliance deadlines vary across jurisdictions, and identifying the necessary steps to ensure compliance.

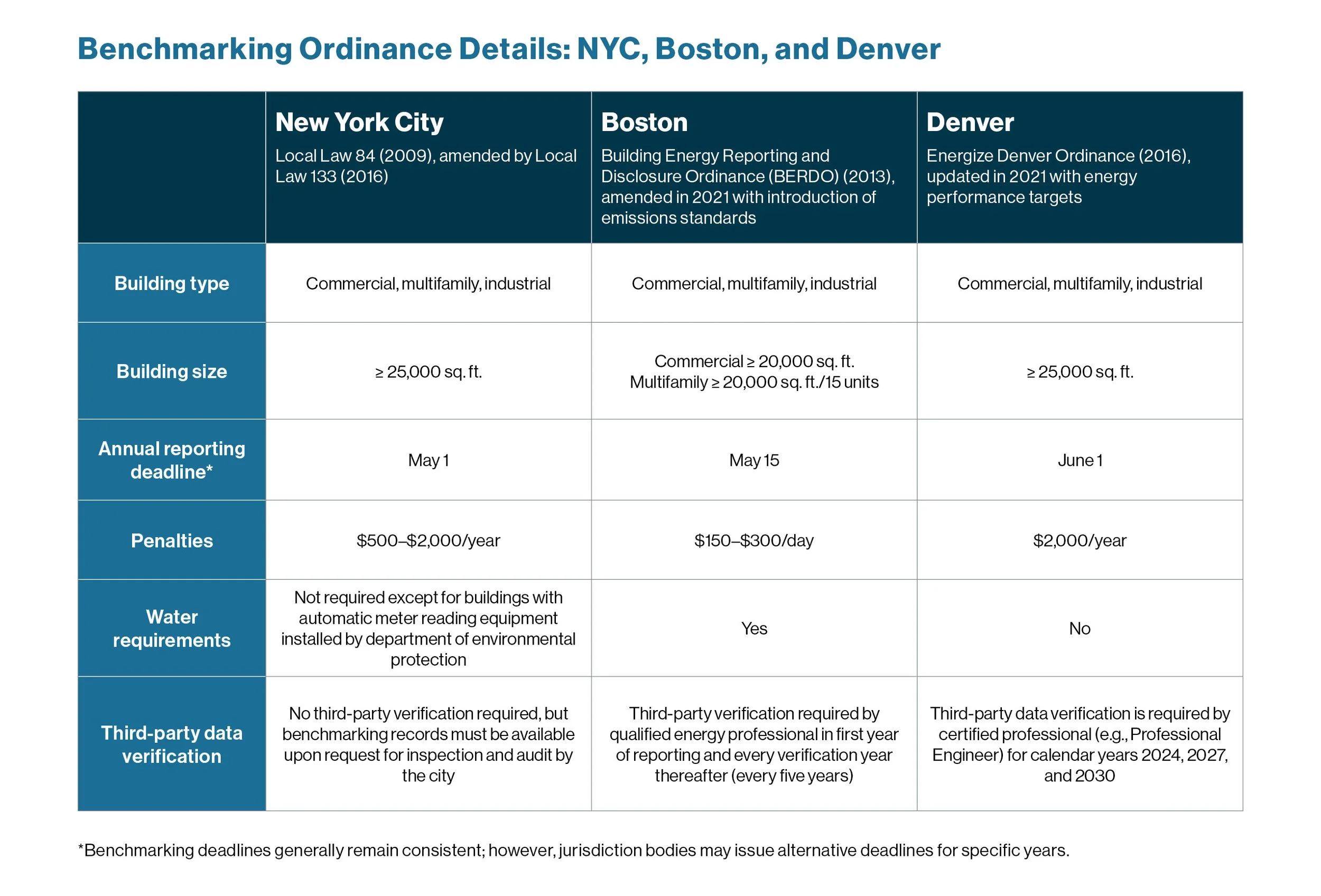

This article will examine how benchmarking, auditing, and BPS are enforced in three key jurisdictions — New York City, Boston, and Denver. These areas face some of the most immediate deadlines and significant implications for property owners.

Sustainable Building Ordinances: New York City, Boston, and Denver

New York City — Local Laws 33, 84, 87, and 97

In 2019, New York City launched its Green New Deal and passed the Climate Mobilization Act, committing to net zero carbon emissions and carbon-free electricity by 2050.[2] To support these goals, Local Law 97 (2019), a key component of the Green New Deal, establishes strict GHG emissions performance standards for commercial buildings that become more stringent every five years. Additionally, prior regulations such as Local Law 84 (2009), which mandates energy benchmarking, and Local Law 87 (2009), which requires buildings to undergo regular energy audits and retro-commissioning, continue to support the city's climate mitigation efforts. Under Local Law 33 (2018), owners are also required to display a letter grade showing the building’s energy efficiency score.

Boston — BERDO

Originally adopted in 2013 under the name Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance (BERDO) as part of Boston's climate strategy, this ordinance required buildings to annually report energy and water usage.[3] To further the city's 2019 commitment to carbon neutrality by 2050, BERDO was amended in 2021 to introduce GHG emissions performance standards.[4] Reflecting this change, the ordinance is now known as BERDO 2.0 (i.e., Boston Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance).[5]

Denver — Energize Denver

After establishing their 80x50 Climate Goal in 2015 (i.e., 80% GHG emissions reduction by 2050), Denver passed a benchmarking law in 2016, the Energize Denver Ordinance, to monitor building energy use.[6] In alignment with Denver’s updated 2021 commitment to reduce 100% GHG emissions by 2040, the Energize Denver Ordinance was updated in 2021 to introduce mandatory energy performance targets designed to achieve net zero energy in existing buildings by 2040.[7] [8] [9]

BPS and Transition Risk: A Case Study of the New York City Real Estate Market

As more U.S. cities align with global climate targets, building owners face growing transition risks — potential financial and operational impacts of the shift to a low-carbon economy. These risks are difficult to quantify without a distinct carbon price. However, BPS in cities like New York City, Boston, and Denver establish a carbon price through penalties, incentivizing owners and operators to implement decarbonization measures.

Looking at the New York City real estate market and Local Law 97, the penalty (carbon cost) for exceeding GHG emissions limits is $268 per ton of CO2 equivalent per year, making the financial implications range from a net benefit to a considerable cost for property owners, depending on the extent of operational measures and retrofits required to meet targets.

According to the September 2023 report, “Getting 97 Done,” issued by Mayor Eric Adams, approximately 25% of buildings predicted to exceed their 2030 limits only need relatively low-cost measures such as weatherization and lighting control upgrades and are expected to save money through energy savings. Meanwhile, 35% will require a mix of low- and high-cost improvements, which remain cost-effective in the long term. Finally, about 40% of buildings are not projected to meet the 2030 targets without comprehensive retrofits; for these buildings, compliance costs vary significantly, ranging from $600 million to $ 2.8 billion, depending on the building type.[31]

The 60% of buildings that can meet their 2030 targets through only relatively low-cost measures and/or a mix of low-cost and high-cost improvements are best suited to make improvements as soon as feasible to capitalize on potential savings in the short-, mid- and long-term. However, the remaining 40% of buildings need to weigh a mixture of financial, market, and reputational risk to decide the amount of retrofitting appropriate to reduce (not necessarily eliminate) penalties.

For some sectors like office buildings, the financial pressures are exacerbated by high operating expenses — averaging $28.67 per square foot, the highest of any U.S. metro area.[32] These costs, combined with post-pandemic revenue challenges due to reduced occupancy rates, make the decision to implement decarbonization measures or pay penalties even more complex.[33]

The complexities of mitigating transition risks in New York City play out in Boston and Denver in similar ways and will continue to show up in U.S. markets as more performance standards are enacted. The approach of each building owner (and building) will be unique and require collaboration between tenants, owners, consultants, incentive programs, and city departments to transform carbon reduction goals and requirements into actions which effectively reduce global carbon emissions.

Options to Adjust Emissions or Energy Limits

New York City: Local Law 97

Per § 28-320.8 of Local Law 97, owners may qualify for adjustments to increase emission limits in 2024–2029 if a covered building is subject to a special circumstance, such as 24-hour operations, high density occupancy, or operations critical to human health and safety. According to the Adjustments Application Filing Guide, the deadline to apply for these adjustments is January 1, 2025.24 As noted in § 28-320.7, adjustments to emissions limits are also possible for a limited period of 1–3 years in a variety of cases where compliance is not possible, such as financial constraints or if carbon offsets are not available at a reasonable price.

In December 2023, the law was amended to specify that “good faith efforts” taken to comply with Local Law 97 will be considered when determining non-compliance penalties. To be eligible for a reduced penalty during the first compliance period (i.e., 2024–2029), owners that have not made sufficient updates to comply with emissions limits must submit a decarbonization plan by May 1, 2025, that details a path to compliance.[34]

Boston: BERDO

To adjust a building’s emissions limits and pathway to net zero emissions, BERDO offers flexibility measures in cases where a building has more than one primary use, an owner has multiple buildings (i.e., portfolio), or if the building is eligible for an Individual Compliance Schedule or Hardship Compliance Plan.

Denver: Energize Denver

On the Flexibility in Compliance page, owners can find information on adjusting EUI performance targets and timelines, electrification incentives, alternative compliance options, renewable energy credits, and compliance assistance for equity priority buildings. To be eligible for a 2024 interim target adjustment before performance evaluation in 2025, owners must apply by December 31, 2024. [35]

Conclusion

The rise of sustainable building ordinances in major urban centers like New York City, Boston, and Denver represents a critical shift towards aligning the U.S. real estate sector with international climate goals. These ordinances, encompassing benchmarking, audits and retro-commissioning, and BPS, not only mandate a reduction in GHG emissions but also push for greater transparency and efficiency in building operations.

As the deadlines for compliance with these ordinances approach, the decisions made by property owners today will determine their ability to meet stringent emissions targets, avoid significant penalties, and contribute to the broader goals of municipal and global climate initiatives. This strategic approach not only aligns with legal mandates but also positions these leaders at the forefront of sustainable management in the face of climate change.

Do you have any feedback on our article? Please take a moment to share your thoughts and suggestions through our short survey.

Authors

Carli Schoenleber

Carli is a Senior Communications Manager at Verdani Partners, where she leads thought leadership, chairs the Engagement Committee, and serves as primary author for Verdani's nonprofit, the Verdani Institute for the Built Environment. With over a decade of experience in the sustainability field, she bridges research and communications to translate complex issues into persuasive messaging and actionable strategies that drive business value and positive impact. Carli holds a B.S. in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management from the University of Minnesota and an M.S. in Forest Ecosystems and Society from Oregon State University.

Dana Weiss

Dana currently serves as an ESG Director for Verdani Partners and leads Verdani's Resilience Committee. She brings 15 years of experience in sustainable design and corporate responsibility. She has developed and implemented ESG policies and protocols for clients across the real estate sector and is currently advising on ESG for over $35 billion in client assets under management. Dana holds a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture and an MBA in Sustainable and Socially Responsible Business.

Kelsey Ceccarelli

Kelsey serves as the co-lead of Verdani Technical Services Department, which completes ASHRAE Energy Audits and other building-level services. Kelsey manages ESG data for four commercial real estate portfolios and acts as a strategic advisor on others. Through tracking buildings’ progress toward sustainability goals, she enjoys seeing the true impact of efficiency in the built environment.

Sydney Armitage

Sydney is an Associate Engineering Manager at Verdani Partners and a co-chair for the Ordinance Committee. She has over 5 years of professional experience in sustainability for the built environment with roles focused on engineering and sustainability program development. She holds a B.A. in Business and Sustainability from Western Washington University.

Rimzhim Mazumdar

Rimzhim Mazumdar is an Engineering Manager at Verdani Partners and a co-chair for the Ordinance Committee.She has over 7 years of professional experience in utility data analysis, project management and sustainability for the built environment. Her expertise and role has been focused on energy engineering and sustainability programs. She holds a Bachelor of Technology in Mechanical Engineering and Master of Energy Engineering from University of Illinois Chicago.

References

[1] Schoenleber, C. (2023). Navigating benchmarking laws and building performance standards in the midst of economic uncertainty. IREM Journal of Property Management. Retrieved from https://jpmonline.org/lean-and-green/

[2] City of New York. (2019). Action on global warming: NYC's Green New Deal. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/209-19/action-global-warming-nyc-s-green-new-deal#/0

[3] City of Boston. (2013). An ordinance amending the Air Pollution Control Commission Ordinance in relation to reporting and disclosure the energy and water efficiency of buildings. Retrieved from https://www.cityofboston.gov/images_documents/Signed%20Ordinance_tcm3-38217.pdf

[4] City of Boston. (2022). Reducing emissions. Retrieved from https://www.boston.gov/environment-and-energy/reducing-emissions#_019-climate-action-plan

[5] City of Boston. (2024). Building emissions reduction and disclosure. Retrieved from https://www.boston.gov/departments/environment/building-emissions-reduction-and-disclosure

[6] City and County of Denver. (2018). Denver 80x50 Climate Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/1/climate-action/documents/ddphe_80x50_climateactionplan.pdf

[7] City and County of Denver. (n.d.) Climate action. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Climate-Action-Sustainability-Resiliency/Cutting-Denvers-Carbon-Pollution/Climate-Action

[8] City and County of Denver. (n.d.) Energize Denver policy timeline. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Climate-Action-Sustainability-Resiliency/Cutting-Denvers-Carbon-Pollution/High-Performance-Buildings-and-Homes/Energize-Denver-Hub/Energize-Denver-Policy-Timeline

[9] City and County of Denver. (2023). Energize Denver benchmarking and energy performance requirements, buildings 25,000 square feet and larger, technical guidance, version 2.0. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/1/climate-action/documents/energize-denver-hub/ed-technical-guidance-buildings-25000-sq-ft-and-larger-v2_june-2023_clean.pdf

[10] City of New York. (2009). Local Law 84. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc2030/downloads/pdf/ll84of2009_benchmarking.pdf

[11] City of New York. (2016). Local Law 133. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/local_laws/ll133of2016.pdf

[12] City of New York. (n.d.). Benchmarking and energy efficiency rating. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/benchmarking.page

[13] City of Boston. (2021). ORDINANCE AMENDING CITY OF BOSTON CODE, ORDINANCES, CHAPTER VII, SECTIONS 7-2.1 AND 7-2.2, BUILDING ENERGY REPORTING AND DISCLOSURE (BERDO). Retrieved from https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2021/12/Final%20Amended%20Docket%200775%20BERDO%202_0.pdf

[14] City of Boston. (2024). BERDO reporting how-to guide. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1bTCjWuJzL-kfmM_nA_sIo9fm5BU5vwihdtbaq8OB3iU/edit

[15] City of Boston. (2024). Building emissions reduction and disclosure. Retrieved from https://www.boston.gov/departments/environment/building-emissions-reduction-and-disclosure#:~:text=BERDO%20applies%20to%20the%20following%20buildings%3A

[16] City and County of Denver. (2021). Rules and regulations governing energy efficiency in commercial and multifamily buildings. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/1/climate-action/documents/hpbh/energize-denver/benchmarking/energize-denver-rules-2021_signed.pdf

[17] City and County of Denver. (2023). City and County of Denver Energize Denver benchmarking and energy performance requirements, buildings 25,000 square feet and larger, technical guidance, version 2.0. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/1/climate-action/documents/energize-denver-hub/ed-technical-guidance-buildings-25000-sq-ft-and-larger-v2_june-2023_clean.pdf

[18] City and County of Denver. (n.d.). Manufacturing, agricultural, and industrial (MAI) buildings. Retrieved from https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Climate-Action-Sustainability-Resiliency/Cutting-Denvers-Carbon-Pollution/High-Performance-Buildings-and-Homes/Energize-Denver-Hub/Buildings-25000-sq-ft-or-Larger/Performance-Requirements/Manufacturing-Agricultural-and-Industrial-MAI-Buildings

[19] City of New York. (n.d.). Energy audits and retro commissioning. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/energy-audits-retro-commissioning.page

[20] City of New York. (2009). Local Law 87. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc2030/downloads/pdf/ll87of2009_audits_and_retro-commissioning.pdf

[21] City of New York. (2020). LL87 of 2009 compliance guide. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/pdf/how_to_file_energy_efficenicy_report.pdf

[22] City of New York. (2019). Local Law 97. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/local_laws/ll97of2019.pdf

[23] City of New York. (n.d.). [LL97] Compliance. Retrieved from https://home.nyc.gov/site/sustainablebuildings/requirements/compliance.page

[24] City of New York. (n.d.). Greenhouse gas emissions reporting. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/greenhouse-gas-emission-reporting.page

[25] City of New York. (n.d.). Local Law 97 covered buildings. Retrieved from https://home.nyc.gov/site/sustainablebuildings/requirements/covered-buildings.page

[26] New York City Department of Buildings. (n.d.). Requirements for reporting annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for covered buildings (1 RCNY §103-14). https://www.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/rules/1_RCNY_103-14.pdf

[27] Boston Air Pollution Commission. (2024). Building emissions reduction and disclosure ordinance, City of Boston code, ordinances, Chapter VII-II.II. Retrieved from https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2024/04/Regulations_1.pdf

[28] Boston Air Pollution Control Commission. (2023). BERDO policies and procedures, version 2.5. Retrieved from https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2024/02/12.20.23%20Full%20Policies%20-%20Clean%20Version_0.pdf

[29] Denver City Council. (2021). A bill for an ordinance amending the Revised Municipal Code of the City and County of Denver to require energy performance and greenhouse gas emissions reductions in existing commercial and multifamily buildings and future electrification requirements for existing buildings. Retrieved from https://denver.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=5196421&GUID=641EBED8-31C9-4CA0-A8F9-946569B7C293&Options=ID%7CText%7CAttachments%7C&Search=21-1310

[30] Denver Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resilience. (2021). Climate protection fund five-year plan. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/2/climate-action/cpf_fiveyearplan_final.pdf

[31] The City of New York Mayor Eric Adams. (2023). Getting 97 done: A plan to mobilize New York City's large buildings to fight climate change. Retrieved from https://climate.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Getting-_LL97Done.pdf

[32] Business Research Division, Leeds School of Business, University of Colorado Boulder. (2022). BOMA 2022 office market study: The impact of U.S. building operations on the economy. BOMA International. Retrieved from https://www.bomadet.org/resources/Documents/ADVOCACY/BOMA%202022%20Office%20Market%20Study.pdf

[33] New York City Comptroller Brad Lander. (2023). Spotlight: What risks does the office market pose for the city’s finances? Retrieved from https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/spotlight-what-risks-does-the-office-market-pose-for-the-citys-finances/

[34] New York City Department of Buildings. (2023, December 12). Notice of adoption of rule. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/pdf/LL88_LL97.pdf

[35] City of Denver. (2024). Flexibility in compliance. Retrieved from https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Climate-Action-Sustainability-Resiliency/Cutting-Denvers-Carbon-Pollution/High-Performance-Buildings-and-Homes/Energize-Denver-Hub/Buildings-25000-sq-ft-or-Larger/Performance-Requirements/Flexibility-in-Compliance

Disclaimer All information contained within this article is protected by law, including, but not limited to, copyright law and trademark law, and none of such information may be copied or otherwise reproduced, repackaged, further transmitted, transferred, disseminated, redistributed or resold, or stored for subsequent use for any such purpose, in whole or in part, in any form or manner or by any means whatsoever, by any person without Verdani LLC’s prior written consent. Verdani LLC does not consent and specifically objects to use of its content to train artificial intelligence (AI) platforms or machine learning algorithms and to inclusion to its content in the knowledge base of Large Language Models (LLMs) and similar AI platforms. Copyright © 2023 Verdani LLC. All rights reserved. This content has been prepared for informational purposes only, and nothing contained herein shall be construed as providing consult or advice. This publication does not take into account specific circumstances of any recipient. This content should not be used as a substitute for consultation with competent professional advisors. Given the changing nature of laws, rules and regulations, the information contained herein is subject to change and may become outdated. While we believe the information contained herein is accurate as of the date of publication and has been obtained from reliable sources, we have not independently verified such information and we are not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the results obtained from the use of this information. This information is provided “as is,” with all faults, and Verdani LLC makes no express or implied representations or warranties, of any kind related to this information. In no event shall Verdani LLC, nor any of its officers, directors and employees, be liable for anything arising out of or in any way connected with the use of this information, whether such liability is under contract, tort or otherwise, and Verdani LLC, including its officers, directors and employees shall not be liable for any indirect, consequential or special liability arising out of or in any way related to the use of this information. References in this publication to websites, resources or tools maintained by third parties are provided for convenience only. Links to those websites, sources or tools do not imply our endorsement of them or their content. We assume no liability for any third-party content contained on the referenced websites.